This is the second in a series of articles that is dedicated to defining a new area for the underwater search of MH370. In the previous article, we presented Bobby Ulich’s overview of a new statistical criteria that supplements the criteria that many investigators have used in the past for evaluating candidate flight paths. In the present article, we present an overview of an exhaustive study principally undertaken by Richard Godfrey, with contributions by Bobby Ulich and me, to examine flight paths with the assumption that after 19:41, the flight was automated and with no pilot inputs. The results indicate that a flight crossing the 7th arc near 34.4S latitude merits a deeper investigation, which will be the subject of the next (third) paper.

What follows are excerpts from “Blowin’ in the Wind”, by Richard Godfrey et al. For more details, please consult the full paper.

Introduction

Following on from Richard Godfrey’s earlier paper entitled “How to play Russian Roulette and Win” published on 13th February 2019, which covered the first part of the flight and diversion of MH370 into the Straits of Malacca, Richard was contacted by Bobby Ulich, who asked the question “where do we go from here?” Richard Godfrey, Bobby Ulich and Victor Iannello came up with the idea to scan the Southern Indian Ocean (SIO) for possible flight paths of MH370 using a degree of precision that we believe has not been previously applied, and to use certain statistical checks on the presence or absence of correlations in the data. Each of us had independently developed a MH370 flight model using the Boeing 777-200ER aircraft performance data, Rolls Royce Trent 892 fuel range and endurance data, Inmarsat satellite data and the GDAS weather data. The goal was to find all possible MH370 flight routes that fit the data within appropriate tolerances. Additionally, the data would be checked using a set of correlations.

Method

Our assumptions about the automated flight after 19:41 are that there are 7 parameters that determine a possible MH370 flight path:

- Start Time

- Start Latitude

- Start Longitude

- Flight Level

- Lateral Navigation Method

- Initial Bearing

- Speed Control Mode

If you draw an arbitrary line of latitude between the area of the last known point and the SIO, MH370 must have crossed this line at a certain time, longitude, flight level and initial bearing using a particular lateral navigation method and speed control mode.

Having fixed the start latitude, the start time and start longitude can be varied for any given flight level, lateral navigation mode, initial bearing and speed control mode, and the fit to the aircraft performance data, satellite data and weather data ascertained. The flight model used in the wide area scan was developed by Richard Godfrey. First the altitude and air pressure at the selected flight level is determined. The GDAS weather data provides the actual surface air pressure and surface air temperature for a given position and time by interpolation. The air pressure for a given flight level is calculated based on the ISA standard surface pressure of 1013.25 hPa and standard surface temperature of 15.0°C. The geometric altitude for a given flight level is then approximated using the actual surface pressure and actual surface temperature. The altitude is used in the satellite data calculations, assuming the flight level is maintained between 19:41:03 UTC and 00:11:00 UTC. Similarly, the GDAS weather data is interpolated for the exact latitude, longitude and time to find the Outside Air Temperature (OAT) and wind at the given flight level.

The scan method for each Lateral Navigation Method (LNAV, CTT, CTH, CMT and CMH) and for each Speed Control Mode (Constant Mach and Long Range Cruise) requires stepping through each possible Initial Bearing (initially from 155°T to 195°T) in steps of 1°T. In Constant Mach (CM) the value was set initially at 0.85 and decremented in steps of 0.01 Mach.

[Note: LNAV = Lateral navigation (following waypoints connected by geodesics); CTT = Constant true track; CTH = Constant true heading; CMT = Constant magnetic track; CMH = Constant magnetic heading]

Once the Initial Bearing and (if relevant) the Mach has been set, the Start Time or Start Latitude is adjusted to minimise the RMS BTO Residual (BTOR) across the 5 satellite handshake points between 19:41:03 UTC and 00:11:00 UTC. The BTOR is the difference between the predicted BTO and the observed BTO. Then the Start Longitude is varied to minimise the RMS BTOR. Finally the Flight Level is adjusted in steps of 1 (standard altitude steps of 100 feet) to minimise the RMS BTOR. A full report is then produced for each scan. (The definition of GSE is found later in the paper, and the significance of the correlation coefficients is based on the work of Bobby Ulich and will be presented in a future paper.)

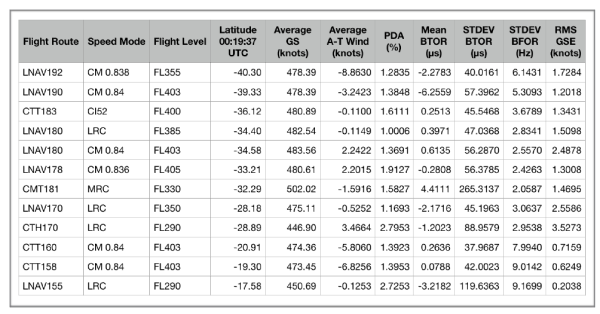

A number of MH370 candidate flight paths have been found over the years by various analysts resulting in Regions of Interest (ROIs) that have either already been searched or have been proposed for a further search. The table below lists some of the ROIs. The table includes some new ROIs which have been found as a result of the current systematic search. Some of the ROIs can be readily dismissed as the standard deviation BTO residual (<47 μs), standard deviation BFO residual (<4.3 Hz) or the calculated PDA (<1.5%) is too high.

Systematic initial bearings from 155°T to 195°T in steps of 1°T were analysed, plus some exotic cases in steps of 0.1°T. All navigation methods were covered: LNAV, CTT, CTH, CMT and CMH, all speed modes: Constant Mach 0.80 to 0.85, LRC 0.7047 to 0.8408, MRC, ECON CI52 and all flight levels: from FL290 to FL430. The fuel endurance was allowed to vary around 00:17:30 UTC and the resulting PDA was noted. The PDA was allowed to vary from the nominal 1.5% and the possibility that the bleed air was shut off for part or all of the time was considered.

In total 1,372 flight paths have been analysed, of which 828 flight paths since the start of this systematic study on 17th February 2019. Start latitudes from 16.0°N to 4.3°S have been covered and the start longitudes were unconstrained. Start times from 18:41:00 UTC to 19:32:00 UTC, but the final major turn had to be completed before the 2nd Arc at 19:41:03 UTC was reached.

Discussion

A more detailed analysis reveals 3 candidate ROIs for further investigation: ROI 1 – LNAV180 CM 0.84 FL403, ROI 2 – LNAV 170 LRC FL350 and ROI3 – CTH170 LRC FL290.

From a pilot’s point of view, a LNAV path on a bearing of 180°T would require setting a final waypoint as the South Pole. This flight path passes close to waypoint BEDAX. The overall fuel endurance and range fits and for a Main Engine Fuel Exhaustion (MEFE) at 00:17:30 UTC, a PDA of 1.37% is calculated (the nominal PDA is 1.5%). The RMS GSE is 2.49, which fits the expected range between 1.0 and 3.0 knots. This flight path ends at 00:19:37 UTC at around 34.5°S near the 7th Arc. This area was originally searched by Go Phoenix but all possible sightings were reexamined and discounted. The search area was widened in later search by Ocean Infinity, but again nothing was found.

An LNAV path on an initial bearing of 170°T starts close to Car Nicobar Airport (VOCX) and passes close to Cocos Island before ending at 00:19:37 UTC at around 28.9°S near the 7th Arc. The overall fuel endurance and range fits and for a MEFE at 00:17:30 UTC, with a calculated PDA of 1.17%. Notably, the Mean BFOR for this flight path is low at -6.87 Hz and is out of the expected range. The area around 28.9°S was searched by Ocean Infinity, but nothing was found.

The CTH path on an initial bearing of 170°T is unlikely as the fuel endurance and range does not fit well. The RMS BTOR is high at 79.6 μs and individual BTOR values are out of normal range. It is also unlikely that a pilot would switch to a True Heading mode. Normal operation is Magnetic Track and this mode is only used for short flight paths, such as during an approach or deviating to avoid bad weather. Switching from Magnetic to True compass mode is only normally done in the region of the north or south poles.

Conclusion

All possible MH370 end points of flight routes in any navigation mode and any speed mode have already been searched, within at least ± 25 NM of the 7th Arc (partially ± 40 NM). This means that MH370 has either been missed in a previous search or recovered from a steep descent of around 15,000 fpm and glided out to an end point outside the previously searched area.

There is only one Region of Interest, where we recommended a further analysis and search at around 34.4 °S near the 7th Arc, following a flight route from close to waypoint BEDAX using the LNAV lateral navigation mode with an ultimate waypoint of the South Pole on a track of 180°T due south, in Long Range Cruise speed mode and at a flight level between FL390 and FL403.

This Region of Interest will be analysed in more depth in the next paper in this series.

@All

Jeff Wise has published an article entitled “The Mystery Behind the Missing Malaysia Airlines Flight Isn’t Solved Yet” dated 28th June 2019.

https://onezero.medium.com/the-mystery-behind-the-missing-malaysia-airlines-flight-isnt-solved-yet-476f65d9b597

In my view, the article is an example of outrageous cheap journalism. There may be gaps in the MH370 story, but there are bigger gaps in the Jeff Wise fantasy.

I believe Blaine Gibson made genuine finds of MH370 debris, as did Johny Begue, Schalk Lückhoff, Neels Kruger, Liam Lotter, Milson Tovontsoa, Rija Ravolatra, Eodia Andriamahery, Jean Dominique, Suzy Vitry, Barry McQade, Jean Viljoen and others. 20 items of debris have been confirmed or are likely to have come from MH370. That these items of debris were flown intact to Kazakhstan, then subsequently damaged to simulate a crash, then subsequently exposed to marine life for a month and finally planted in 27 locations in 7 countries for 14 different people to find, is preposterous nonsense.

Blaine has travelled to 185 countries and speaks 6 languages fluently including Russian. This is not proof of anything suspicious. I have travelled to 130 countries and speak 4 languages fluently.

It is public knowledge that Blaine worked on various government sponsored projects between the US and Russia from 1998 until 2005. This included the US independent verification of the Russian reform of the Atomic Industries Enterprises (including the Atomic Weapons Program), which was based in the closed Russian Nuclear Cities of Snezhinsk, Zarechny and Obninsk. Blaine was based in Washington DC and Seattle, but travelled extensively to Russia. Blaine has not travelled to Russia in the last 15 years. There are many international verification programmes which include US citizens travelling to Russia, which are in operation even today. This is not proof of anything suspicious. I have also travelled to Russia. I have also worked on government sponsored projects.

It is public knowledge that Blaine set himself up as a consultancy and trading company, called the Siberia-Pacific Company in 1992. The company is registered at his home address in Seattle, with Blaine as President. US trade with Russia in 1992 was 2.6B$ and in 2018 had reached 27.5B$. Siberia-Pacific has been inactive for the last 20 years and was dissolved last year. This is not proof of anything suspicious. I am a one man consultancy company registered at my home address. I have done business in 17 different countries.

It is public knowledge that Blaine Gibson sold his parent’s home in April 2014 for $1,185,000. This would easily fund travels to various locations bordering the Indian Ocean. This is not proof of anything suspicious. It is not uncommon for children to inherit from their parents.

One Russian and two Ukrainian passengers on MH370 is not proof that MH370 was sabotaged. There were 14 different nationalities on board (not counting stolen passports from Austria and Italy). It may come as a surprise to Jeff Wise, but Russians travel too. There are flights from Russia to 110 international destinations. The volume of International flights is only surpassed by the USA. This is not proof of anything suspicious.

You may think what you will of the Jeff Wise fantasies, but his personal attack on Blaine Gibson is unfounded, deceitful, actionable and divisive. I am sure you would all join with me in defending Blaine Gibson’s integrity and his great service in helping to solve the mystery of MH370.

@TBill: In the PMDG 777 model, if you remove power from the left bus, you will see the message DATALINK LOST, among other messages. However, in the model, I don’t know a way to shutdown the ACARS without removing power to the entire SATCOM. There’s only so much realism you can expect in low-cost software.

@Richard Godfrey: Well said. Jeff Wise’s continued attacks on Blaine Gibson are despicable. Unfortunately, Blaine’s reputation is collateral damage in Wise’s futile attempt to prop up a long-discredited theory.

Thanks Richard. Jeff Wise’s attacks on Blaine and William are totally without merit. I agree with Victor that those comments are nothing more than a desperate attempt to prop up Jeff’s nonsensical theories about MH370. He should be ashamed for his statements, and his acts.

“All possible MH370 end points of flight routes in any navigation mode and any speed mode have already been searched, within at least ± 25 NM of the 7th Arc (partially ± 40 NM). This means that MH370 has either been missed in a previous search or recovered from a steep descent of around 15,000 fpm and glided out to an end point outside the previously searched area.” Yet your table above shows a path 192 ending at 40.3S. My preferred route, as previously mentioned is ~191 and ends just shy of 40S. Neither searched at any width. I am also surprised that far from being infeasible on fuel, as has been so often asserted, this table appears to show feasible pda. I’m not clear why these non-searched latitudes of roughly 39.5-40.5S would not be at the top of the list!

I am also surprised at how great the max/min and rms BTO errors are on your shortlisted 3. These are not particularly good BTO fit compared to other path solutions, c.f. Vi’s great circle paths paper, showing the most southern routes with best BTO fit (rms in the low 20s).

@Paul Smithson

You state: “Yet your table above shows a path 192 ending at 40.3S.”

The table was showing the list of all candidate regions of interest from various analysts over the years. “A number of MH370 candidate flight paths have been found over the years by various analysts resulting in Regions of Interest (ROIs) that have either already been searched or have been proposed for a further search.”

You ignore the statement that follows in both Victor’s article and in the paper “Some of the ROIs can be readily dismissed as the standard deviation BTO residual (<47 μs), standard deviation BFO residual (<4.3 Hz) or the calculated PDA (<1.5%) is too high."

The LNAV192 route that you reference has a standard deviation BFO residual of over 6 Hz. This is too high in my view and disqualifies the route.

The reason that non-searched latitudes of roughly 39.5-40.5S are not at the top of the list is because in general the BTO residuals and BFO residuals are too high (please see Figure 16 and 17 in the linked paper).

You further state "My preferred route, as previously mentioned is ~191 and ends just shy of 40S."

I will be pleased to run a flight path LNAV191.0 CM 0.84 FL410 through my model if you wish, or would you prefer a different initial bearing, navigation mode, speed mode or flight level?

In any case, at this stage we are only making an initial recommendation and all possible ROI candidates will be evaluated again in more detail.

@Paul Smithson

You stated “I am also surprised at how great the max/min and rms BTO errors are on your shortlisted 3. These are not particularly good BTO fit compared to other path solutions, c.f. Vi’s great circle paths paper, showing the most southern routes with best BTO fit (rms in the low 20s).”

The purpose of the paper presented here is to give the results of the wide scan search.

Victor’s purpose in his article on great circle paths in 2017 was evaluating specific flight routes.

Bobby has pointed out that the goal is not to find a flight route with all BTORs = 0 µs and all BFORs = 0 Hz.

Again I repeat my offer to run a flight route of your choosing through my model, so we can compare the results of your model and mine.

@Richard

Using BFOR as a route qualifier is not sound from a mathematical standpoint for reasons I have voiced here several times (BFO data is neither stationary nor ergodic and STDEV should not be used). Because one can compute a BFOR does not mean that it has significance.

Your CTT160 and CTT158 routes look very good otherwise.

Richard Godfrey: “finally planted in 27 locations in 7 countries”

I don’t think JW ever stipulated that. The debris doesn’t need to be planted at different times in different places, but it would be enough to throw it all into the water somewhere, preferably somewhere near ARC7 and let the currents do the rest.

@DennisW,

You said: “Using BFOR as a route qualifier is not sound from a mathematical standpoint for reasons I have voiced here several times (BFO data is neither stationary nor ergodic and STDEV should not be used). Because one can compute a BFOR does not mean that it has significance.”

You keep repeating the same mistakes and reaching the same, and incorrect, conclusion. This has previously been discussed at length on this forum by Mike and me in comments made specifically to you.

Here (again) are the FACTS:

1. The BFO reading noise comprises multiple components, including random electronic noise in the GES frequency measurement equipment, pseudo-random frequency errors impressed on the transmitted frequency by limited precision trigonometric functions in the frequency compensation algorithm in the AES, and frequency drift (frequency noise) in the OCXO in the SDU.

2. The frequency drift of the OCXO is characterized by the Allan variance, and it is non-ergodic and non-stationary.

3. The time scale for the OCXO Allan variance (i.e., the OCXO frequency drift) to become significant or dominant relative to the other sources of BFO reading error is days.

4. Applying the specified Allan variance for the OCXO on short time scales (seconds to minutes) shows that the expected magnitude of OCXO frequency drift is smaller than the observed BFO reading errors by several orders of magnitude.

5. On time scales of hours or less (i.e., during a single flight) the Allan variance effect is a negligible portion of the observed BFO reading errors. Thus DSTG’s Figure 5.5, which is the observed probability density function of BFO reading errors, is insignificantly affected by the OCXO Allan variance. That is because the mean value has been removed for each flight, which effectively removes the OCXO frequency drift characterized by the Allan variance.

6. Thus, BFO best-fit residuals, for a single flight, which lie outside the boundaries of the the PDF in Figure 5.5 are indicative of route parameter errors (NOT OCXO drift).

7. Thus, fitted BFO residuals are useful in evaluating routes during a single flight.

8. Thus, Richard (and DSTG and everyone else who has ever built a route fitter) is correct to use the BFO residuals (other than the mean value) as a route discriminator.

@Peter Norton

You stated “Richard Godfrey: “finally planted in 27 locations in 7 countries” I don’t think JW ever stipulated that.”

That is exactly what Jeff Wise stated and he names Blaine Gibson and the Russians as the perpetrators:

(1) Jeff Wise 14th April 2016

http://jeffwise.net/2016/04/14/mh370-debris-was-planted-ineptly/

“There is only one reasonable conclusion to draw from the condition of these pieces. Since natural means could not have delivered them to the locations where they were discovered, they must have been put there deliberately. They were planted.”

“Given how little inquiry had been directed at the Réunion piece, whoever planted the most recent four pieces might reasonably have assumed that the public would accept the new pieces uncritically, no matter how lackadaisical their preparation.”

“So maybe whoever planted the debris in Mozambique, South Africa, and Rodrigues weren’t lazy–maybe their understanding of human psychology simply allowed them to take the minimum steps necessary. Whether their calculation was accurate or not will now become apparent.”

(2) Jeff Wise 29th April 2016

http://jeffwise.net/2016/04/29/mh370-debris-questions-mount/

“I understand that not everyone is ready to accept that the absence of marine life can only mean that the debris was planted.”

(3) Jeff Wise 16th October 2016

http://jeffwise.net/2016/10/16/what-if-zaharie-didnt-do-it/

“Granted, we are still left with the issue of the MH370 debris that has been collected from the shores of the western Indian Ocean. Many people instinctively recoil from the idea that this debris could have been planted”

(4) Jeff Wise 10th December 2016

http://jeffwise.net/2016/12/10/is-blaine-alan-gibson-planting-mh370-debris/

“I find it quite extraordinary that a purported piece of MH370 apparently washed up on the shore within half an hour of Blaine’s passing by the spot.”

(5) Jeff Wise 10th March 2019

http://jeffwise.net/2019/03/10/who-is-blaine-alan-gibson/

“If the hijacking of MH370 was a Russian plot, and MH370 flew to Kazakhstan, then the pieces of debris collected in the western Indian Ocean must have been planted by the Russians in an effort to support the misleading southern narrative. Blaine Alan Gibson had demonstrated an uncanny knack for locating and publicizing this debris. Was Gibson somehow connected to Russia?”

(6) Jeff Wise 28th June 2019

https://onezero.medium.com/the-mystery-behind-the-missing-malaysia-airlines-flight-isnt-solved-yet-476f65d9b597

“But Langewiesche finds the idea of planting evidence inconceivable — mainly, it seems, because a large proportion of the debris was found by an American named Blaine Alan Gibson. And here, I think, is where his story really goes off the rails.”

@Niels

You asked “Could you perhaps help to evaluate the proposed route (21:11:02 onwards)?”

The key parameters of your case C are as follows:

– LRC to fuel exhaustion.

– FL 335.3.

– 21:11:02 position of 9.191°S, 93.692°E.

– Constant track after 21:11:02 of 178.098 degrees.

Here are the results for MH370 Flight Path Model V19.7 RG CTT LRC FL335.3 178.098 Niels Case C:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/xmavpyw8hzixug4/MH370%20Flight%20Path%20Model%20V19.7%20RG%20CTT%20LRC%20FL335.3%20178.098%20Niels%20Case%20C%20Full%20Report.png?dl=0

The BTOR, BFOR and PDA all appear to fit from 21:11:02 UTC onwards.

I will examine similar flight paths CTT178.098 LRC FL335.5 from 19:30 UTC onwards with a full set of correlation coefficients.

Re BFO. I thought that the consensus now was that BFO error under ~7hz should not be considered as a “hard discriminator”, although lower BFO errors would be expected/preferred. Dr B says that oscillator drift occurs only over longer timescales and appears to be saying that BFO is “back in the game” as a hard criterion for solution selection. Do others with expert knowledge of oscillator characteristics agree? Dr B, does your view still hold in the case of an oscillator that has been power-cycled? With the possibility of much colder ambient temp (and temp gradients within the temp-stabilised casing)?

Re Fuel. I am also confused (but pleasantly surprised) that 40S seems to be fuel feasible (PDA 1.3 – 1.4). In previous correspondence, Dr B was adamant that this was not even remotely reachable, even with packs off. Could one of the authors please explain how the estimate of fuel requirement for southerly paths has changed so radically?

@Paul Smithson

(1) Re BFO please see the comment from DrB at 04:40 am today (above).

(2) Re PDA it has not changed, Bobby, Victor and I all have different models.

(3) I note you have declined my offer to model a flight path of your choosing.

(4) What results does your model give for your preferred path ca. 191, in particular for BTORs, BFORs and PDA?

@DrB

The time scale for the OCXO Allan variance (i.e., the OCXO frequency drift) to become significant or dominant relative to the other sources of BFO reading error is days.

You might want to check out figure 5.4 of the DSTG book. The random walk behavior of quartz oscillators begins at about 100 seconds.

https://photos.app.goo.gl/uxMW4mxeoagvGr1S7

@DrB

You might also ponder why no oscillator manufacturer uses mean and variance (Gaussian statistics) to characterize oscillator behavior.

@DennisW,

You continue to ignore actual facts.

First you said: “You might want to check out figure 5.4 of the DSTG book. The random walk behavior of quartz oscillators begins at about 100 seconds.”

The feature displayed in Figure 5.4 has already been explained (to you directly) by @airlandseaman. He was told that less-than-2-hour excursion was not identified on other flights and actually repeated ( i.e., re-traced) on the return flight. DSTG properly concluded it had a different cause than oscillator drift.

Even if oscillator drift begins at 100 seconds, that does not demonstrate it was significant in amplitude. In fact, we do know that occasionally drifts of 16 Hz occurred over periods typically of several days (about 172,800 seconds). Over a period of 100 seconds, the same oscillator would exhibit an amplitude reduction by a factor of SQRT(100/172,800) = 42. So at 100 seconds the worst-case amplitude could be as large as 16/42 = 0.4 Hz, and thus be insignificant compared to other BFO reading noise sources (which have nothing to do with the OCXO).

You also said: “You might also ponder why no oscillator manufacturer uses mean and variance (Gaussian statistics) to characterize oscillator behavior.”

You continue to conflate oscillator frequency noise with BFO reading error. They are NOT the same thing. You continue to ignore the fact that the BFO reading error is NOT dominated by OCXO frequency drift during a single flight. The major contributors to BFO reading error DO have repeatable statistics, including mean and standard deviation.

@Richard. Thank you for taking the time to respond. However, your defensive tone implies that you read some sort of veiled offense into my remarks?

1) Yes, it was to that post that my query referred. And you didn’t answer the question

2) I’d like to hope that your different models don’t produce answers that vary +/- 2 percentage points PDA.

3) Where did I say that I had declined your offer?

@paul smithson,

You said: “Dr B, does your view still hold in the case of an oscillator that has been power-cycled? With the possibility of much colder ambient temp (and temp gradients within the temp-stabilised casing)?”

As I have previously explained, there is no reason to think the frequency drift characteristics of the OCXO would be changed by thermal cycling. I do allow the BFO bias frequency to be different after 18:24 to accommodate the possibility that the SDU was cold soaked to -55C during the previous hour. We now know that the change in bias frequency compared to take-off was at most 3-4 Hz, so either the cold soak did not occur or it did not shift the OCXO frequency substantially.

@Paul Smithson

When did you accept my offer or answer my question regarding your model?

@DrB

The feature displayed in Figure 5.4 has already been explained (to you directly) by @airlandseaman. He was told that less-than-2-hour excursion was not identified on other flights and actually repeated ( i.e., re-traced) on the return flight. DSTG properly concluded it had a different cause than oscillator drift.

I don’t recall that exchange, but I will take your word for it. Was the cause ever explained or are you choosing to simply ignore it? If we had the data from previous flights we could characterize typical BFO error associated with oscillator drift. As it stands I would not use BFO as a path qualifier.

@DennisW,

DSTG determined that particular event had a “geographical dependence”. They never identified a specific cause, nor were similar occurrences noted. DSTG does not say whether this event was included in the histogram in Figure 5.5, which is what I used for my BFOR reading error model.

If you ever create a route fitter, you are free to choose whatever criteria you wish to use. However, as I have said before, the major value of the BFOs is to require a Southern Hemisphere solution. With only that, the answer is unchanged. The only ROI which is consistent with all the data is LNAV 180. Adding the standard deviation of the BFORs produces stronger rejection of more southerly and more northerly routes, but these are also rejected without the BFORs.

@DrB

“determined” = “speculative”. No matter. I am off this subject. Be careful :-).

Dr B. Thank you for your response. I understand you to be saying that a step-change of bias freq after cold-soak is conceivable, but not drift of growing amplitude. I’m not sure what the basis is for your confidence that “We now know that the change in bias frequency compared to take-off was at most 3-4 Hz”? Could you please elaborate?

@Richard

Thank you for evaluating “Case C”. The results are encouraging. The main difference with “Case A” is that for each chosen FFB (in the range of 150 Hz – 153 Hz with 0.5 Hz steps), I minimized the variance(track) for the interval 21:11 – 00:19 instead of for the interval 19:41 – 00:19 [by varying the starting lat, lon only]. This results in a much straighter track in the 21:11 – 00:19 interval.

Furthermore I select the flight level for each FFB/path by subsequently minimizing the mean error in TAS (error defined as the difference between calculated TAS and expected TAS for LRC). The path (FFB) that is finally selected as “optimum” is the one having the smallest RMS(delta_TAS). The key parameters (FL, mean track and 21:11 position) are directly extracted from the data sheets.

Note that the path estimator indicates a path roughly from BEDAX through ISBIX to the 21:11 position (ISBIX pass around 19:57 UTC) and a settling at the near 178 degrees track in the vicinity of the 21:11 position, which is less than 100 nm north of BEBIM. The speed profile indicates that perhaps the FL was gradually increasing until about the 21:11 position as well (and then settled at a constant level). The indicated 19:41 position is 2.36, 93.75 (BTO calculation for 11 km) at a GS of about 432 kts.

Finally: this is all based on a “best fit” interpolation of BFO and BTO data, which not necessarily represents the “true” BFO and BTO curves.

@paul smithson,

You said: ” I’m not sure what the basis is for your confidence that “We now know that the change in bias frequency compared to take-off was at most 3-4 Hz”? Could you please elaborate?”

This conclusion is based on the fact that all ROIs which show > 1% probability of being the True route also have 19:41-00:11 mean BFORs near -3 Hz.

Dr B. Thanks for the response. But is there not a degree of circularity in that reasoning? I’d be more comfortable with some experimental evidence of the behaviour of the equipment in question.

@Paul Smithson said: I’d be more comfortable with some experimental evidence of the behaviour of the equipment in question.

There is experimental evidence of a shift in frequency bias after a power up for the SDU on 9M-MRO. From a previous post:

It turns out there is an effect called “retrace” that causes oscillators that are powered down, cooled, and powered up to shift in frequency, and there are indications that a retrace shift of about -4 Hz occurred while 9M-MRO was on the ground at KLIA before the MH370 flight. A similar shift, but in the opposite direction (up) might have occurred due to the inflight power cycling.

@Victor @Richard

Catching up on my reading, do we have handy link to “How to play Russian Roulette and Win”…trying to recall if I read that paper.

@paul smithson,

You said:”Dr B. Thanks for the response. But is there not a degree of circularity in that reasoning?”

Actually, no there isn’t. The few ROIs which show a significant probability of being the True Route, when the BFORs are not included at all in the statistics list, have mean BFORs near -3 Hz. Those same ROIs also have the best match to the expected BFOR standard deviation.

@Richard:

re debris: thank you, I stand corrected

@DrB

@Richard

Gents, like Paul, I was very surprised to read that there are sub-39°S termini returning feasible PDAs. I’m sure that I can recall previous discussions where DrB’s fuel flow model effectively limited termini to around 38.5°S.

Is there a different base assumption between DrB’s earlier work and Richard’s most recent work that explains the difference?

@Andrew Just to say thank you very much for your helpful reply to my comment on the previous blog about the 737 Max. I have only just seen it. I appreciate the time you took to explain. Thanks! Julia

@Mick Gilbert, @Paul Smithson

The fuel endurance and fuel range calculations are complicated and based on many assumptions.

The last ACARS message at 17:06:43 UTC shows that the aircraft Gross Weight was 480,600 lbs (rounded to the nearest 100 lbs) and the Fuel Weight was 43,800 kg (rounded to the nearest 100 kg). This would make the aircraft Zero Full Weight (ZFW) 217,997 kg – 43,800 kg = 174,197 kg. The Malaysian Safety Investigation report states the ZFW is 174,369 kg. What was the precise amount of fuel at 17:06:43 UTC? What was the ZFW? What was distribution between the fuel tanks?

The last ACARS message was at 5.299°N 102.813°E at 35,004 feet and before the diversion after waypoint IGARI. The flight path between 17:06:43 UTC and 18:22:27 UTC is not precisely known, the flight path between 18:22:27 UTC and 19:41:03 UTC is not known at all and the flight path between 19:41:03 UTC and 00:19:37 UTC is not precisely known. What speed mode was selected? What navigation mode was selected? What Flight Level was selected? Was there any climbs or descents? Was there any step climbs? Was there an intermediate landing or attempted landing?

The fuel used is dependent on time, aircraft weight, fuel flow coefficients, temperature deviation from ISA, Mach, Performance Degradation Allowance of each engine, speed mode (Constant Mach, LRC, MRC, ECON, etc) and other loads on the engine (Integrated Drive Generators, Bleed Air System). We are told in a Rolls Royce report that the right engine fuel consumption is greater than the left engine fuel consumption. Was there any fuel transfer between tanks? What was the actual PDA of each engine?

The TAS for a given Mach depends on the Outside Air Temperature (OAT) at the Flight Level chosen. The Ground Speed depends on the navigation mode, Wind Speed and Wind Direction. The range will depend on head/tail/cross winds encountered over the whole flight path. I use the GDAS weather data, but this is only available every integer degree of Latitude and Longitude, every 50 hPa of Pressure Altitude and every 3 hours in time. A quadrilinear interpolation has to be made. I analysed the dynamic in the GDAS for the MH370 solution space from 15°N to 40°S and from 80°E to 105°E, from 150 hPa to 350 hPa and from 18:00 UTC to 03:00 UTC+1. (1) As you would expect, the OAT changes predominantly with Altitude by on average -10.37°C per 50 hPa (worst case -17.1°C), but little over 1° Lat/Lon or time (worst case -3.6°C over 1° Lat). (2) The Wind Speed changes predominantly with Time and Altitude (worst case -120.74 knots over 3 hours), but less over 1° Lat/Lon (worst case -34.68 knots over 1° Lat). (3) The Wind Direction changes significantly with Time, Latitude, Longitude and Altitude (worst case ±180.0°T). I analysed the ACARS vs GDAS for MH371. During one stable part of the cruise, the differences between the GDAS model and the actual ACARS data were as follows: The OAT Actual – Predicted had a Mean Error of -1.0 °C and Standard Deviation of 2.5 °C. The WSPD Actual – Predicted had a Mean Error of -0.8 knots and Standard Deviation of 1.3 knots. The WDIR Actual – Predicted had a Mean Error of +1.6 degT and Standard Deviation of 6.8 degT. What was the actual weather data for a particular flight path? What is the accuracy of the GDAS data used to model a particular flight path?

I do not claim to have made all the right assumptions or correct calculations. Bobby’s fuel model is probably more accurate than mine and Bobby certainly simulates the end of flight more precisely with the INOP after the first engine flame out prior to 00:11:00 UTC and MEFE after the second engine flame out at around 00:17:30 UTC more precisely than I do, with the resulting engine restart attempts, APU start, speed reduction and altitude loss. We agree quite closely on the aircraft and fuel weight at 19:30 UTC. There are small differences in the temperature and winds over the course of the next ca. 5 hours of flight. There are large differences in the end of flight simulation.

I am genuinely open to see whether a flight path as proposed by Paul Smithson at 191° to 40°S fits the data we have. As you can see, there is a huge difference between a LNAV191, CTT191, CTH191, CMT191 or CMH191 path. There is also a huge difference between a LNAV191 CM 0.84 FL410 and a LNAV191 LRC FL350. There is no generic statement that all 191 flight paths fit the fuel data or not.

@Julia Farrington

You’re very welcome!

@TBill

You asked: “Catching up on my reading, do we have handy link to “How to play Russian Roulette and Win”…trying to recall if I read that paper.”

The link to the paper can be found in this comment:

http://mh370.radiantphysics.com/2019/01/12/mh370-flight-around-penang/#comment-21779

@Paul Smithson

You stated:”@Richard. Thank you for taking the time to respond. However, your defensive tone implies that you read some sort of veiled offense into my remarks?”.

Thank you for taking the time to criticise the new paper.

Your offensive tone was not veiled. You started to throw rocks at the new paper, less than 2 hours after publication.

Since you meanwhile complain, that I was wrong to say that you had rejected my offer, when are you actually going to answer my question regarding the key parameters of your proposed flight path and accept my offer to model your flight path? I only need to know navigation mode, flight level and speed mode.

I wanted to compare your results with mine.

@Richard

Very nice paper…I like that Feb_2019 “Russian Roulette” paper very much. I will have some questions upon further review. Briefly, I am thinking, yes, Left and Right buses off at IGARI to go dark and maybe cut off DCDR recording session, and perhaps other side benefits. This potentially ties in with William Langewiesche’s recent article where, if I undertsand, he suggests all power off at IGARI.

Correction: DFDR (flight data recorder)

@Mick Gilbert,

You said:”Gents, like Paul, I was very surprised to read that there are sub-39°S termini returning feasible PDAs. I’m sure that I can recall previous discussions where DrB’s fuel flow model effectively limited termini to around 38.5°S.

Is there a different base assumption between DrB’s earlier work and Richard’s most recent work that explains the difference?”

Neither Richard’s paper nor his comments say the PDA is acceptable for routes ending circa 40S. In fact, those routes have unacceptable BTO residuals, unacceptable BFO residuals, and unacceptable PDAs.

Richard’s subsequent comment aptly summarizes all the aircraft and environmental factors which affect fuel consumption. There is a Region of Interest (ROI) at 191/192 degrees for “straight” paths. This route requires very high true air speed in order to roughly match the BTOs. Very high air speed results in a serious degradation in fuel mileage, and, using my fuel model, this produces a large fuel shortfall (~5%) for this ROI, ending circa 40.3S. This fuel shortfall cannot be fully compensated by turning off bleed air and one IDG. If one ignores the BTOs and flies slower at MRC, the range is maximized and 40S becomes marginally possible with bleed air off. However, the disagreement in BTOs is hopelessly large. So, it’s one thing to draw a maximum range arc, and then extend it by several percent assuming bleed air was off the entire time after circa 17:30, but such a route is incompatible with both BTOs and BFOs

@TBill

You stated: “@Richard Very nice paper…I like that Feb_2019 “Russian Roulette” paper very much.”

Many thanks!

It is encouraging to receive a compliment.

This is especially true since the “Russian Roulette” paper took 6 weeks to produce and the “Blowin’ in the Wind” paper took 4.5 months to produce.

@Peter Norton

You stated “@Richard: re debris: thank you, I stand corrected”

No worries! It takes a Gentleman to say, “I stand corrected”.

@Richard & co-authors

Many thanks for sharing your new paper, summarizing past months systematic scan for flight paths that fit the data “within appropriate tolerances”. It is an impressive and important effort, which deserves careful reading. I’m still studying some parts more in detail, however for now on one point I would like to ask you to explain a bit further.

In the discussion part, the ROI 1 is mentioned (LNAV180 CM 0.84 FL403), which seems to be a bit high on the STDEV BTOR.

In the method part, at slightly lower FL390 and LRC speed setting, fig. 4 and fig. 5 give slightly lover values for STDEV BTOR / RMS BTOR.

In the conclusions reference is made to “Long Range Cruise speed mode and at a flight level between FL390 and FL403”.

Should I read from this that some optimization is still ongoing regarding the LNAV180 path? What is the typical margin on the 7th arc latitude?

@Richard

@DrB

Thank you, gentlemen, for your separate responses. Much appreciated, as always.

@Richard

It is encouraging to receive a compliment.

It is, indeed. Even more important is a careful read, and considered feedback. As a VP in a previous life responsible for a significant P&L, I nevertheless sat through every design review and code review. It sent a strong message to the team that I considered them to be important, and I took the time to prepare with diligence.

As you know (or should know), I have a high regard for your work. The fact that I am critical of your (and DrB’s) recent efforts is not a reflection on your competence (or DrB’s). It is simply my deep seated belief that a reliance on BFO as a path qualifier is a mistake. I would be happy to be wrong, and there is ample precedence for that.

However, to not comment would be out of character for me. I am too old for that.

@DrB

Bobby, I understand that you are saying that Richard’s LNAV192 CM0.838 FL355 route terminating at 40.30S has unacceptable BTO and BFO residuals but the PDA for that route is 1.2835%.

Given that the nominal PDA is 1.5%, is 1.2835% unacceptable?

@Mick Gilbert,

My LNAV 192.26 route at M0.84 and FL355 ends at S40.3 and has a PDA of -4.1% for a MEFE at 00:17:30. That PDA is obviously unacceptable, and that is why I said so. The PDA will be reduced in order to accommodate the high air speed, relatively low altitude, and elevated SAT on this night on this route, all of which increase the fuel flow.

Richard’s value for PDA, as given in the table in this post and which you quoted, is much different. We shall investigate this difference and report back.

@Mick Gilbert: To look at the PDA for a path that has unacceptable BTO error doesn’t have much meaning (unless you are questioning our understanding of the BTO values).

In the previous article on great circle paths, which limited the survey to FL350, by observing Figure 2 and the results in the CSV file, you can see that for a track angle of 192° at 19:41, the paths cross the 7th arc near 40S latitude. If the speed mode is constant Mach number, the BTO error is acceptable (21.3 μs RMS), but the required speed is M0.842, which is substantially higher than LRC speed, and there is insufficient fuel. (For the time period after 19:41, LRC corresponds to an average speed of about M0.81.) On the other hand, if the speed mode is LRC, less fuel is consumed, but the BTO error increases to 91.7 μs, which is unacceptable. It is misleading to consider fuel consumption without also considering BTO error.

@Mick Gilbert @Paul Smithson

My apologies!

The entry for the LNAV192 CM 0.838 FL355 in the table above is not correct.

This values came form an old version of my model by mistake.

I have checked this flight path again with my latest version.

Bobby is right that this flight path does not fit the fuel consumption, BTORs or BFORs.

I also get a negative PDA for a MEFE at 00:17:30 UTC, high BTORs and high BFORs.

I will run a thorough check on all the values in the table.

This flight path candidate remains disqualified, even more so than before.

@Victor Iannello

Thank you Victor. No, I am not questioning our understanding of BTO values.

I am not interested in fitting a route. What I am interested in is establishing the southernmost bound on the 7th arc based on the fuel modelling. I thought that had been established at around 38.5°S. Richard’s recent paper seemed to call that into question.

Accordingly, what I was questioning was the apparent marked difference between the PDA values as originally published by DrB and those published by Richard for not overly dissimilar routes.

DrB has acknowledged that difference and will investigate. I will standby to stand by.

@Richard

@DrB

Okey doke, thanks Richard.

That issue aside, your paper (like the many that have gone before it) represents a considerable body of work and scholarship. It was somewhat remiss of me not to have acknowledged that earlier.

Similarly, I was remiss in not acknowledging DrB’s earlier work on the fuel modelling.

So, a formal thank you to you both and a thank you to Victor for making the your efforts and the ensuing discussions widely accessible.

@Richard, I am glad that you have identified the reason for the apparent discrepancy on fuel feasibility of the 190-192 paths.

@Mick Gilbert

Many thanks for your kind words and thanks.

@Niels

You asked: “Should I read from this that some optimization is still ongoing regarding the LNAV180 path? What is the typical margin on the 7th arc latitude?”

(1) Yes, we are still comparing models in a comprehensive test program. There may be minor adjustments to come.

(2) Our 3 models are very close for the LNAV180 LRC FL390, but subject to a number of assumptions. Bobby is doing a sensitivity analysis and we will then be in a better position to state typical margins.

@Mick Gilbert,

My work on the fuel flow modeling took over 1,000 hours and 10 months to complete. However, it would not have been possible to achieve the desired accuracy were it not for data provided me by ATSB under a non-disclosure agreement and also non-public B777 information provided me by a confidential source. Both were extremely helpful.

Some comments on PDA

PDAs, in the way that they have been calculated in the recent work by Richard, DrB and Victor, are are a useful discriminator in validating, or eliminating, possible flight tracks. However, what is being calculated is not actually a PDA at all. Rather it is a variation, or delta, from the fuel burn that would normally be expected from Boeing data that would apply to the particular circumstances relating to speed, altitude, temperature, pressure, wind etc, etc, and will include actual differences in engine efficiency from nominal, for for the flight track in question.

PDA, on the other hand, is the Performance Degradation Allowance used in flight planning to determine the additional fuel to be uplifted, making an allowance for the age, and hence the reduction in efficiency from a new (maybe nominal) engine. The PDA for every engine can therefore be different, but by definition the PDA will never be negative. Because it is not unusual for engines on a particular airframe to have significantly different Time in Service, I suppose it is also possible that the PDAs might be averaged for flight planning purposes.

I think we know, both from ACARS data, and from other sources (and DrB is privy to other information) that the “average” PDA for MH370 is of the order of 1.5%. I think we also know that it would be unusual for the PDA of any engine to exceed 3%. But it can’t be negative.

If, as a result of the modelling it is determined that the delta in fuel burn for a particular track turns out to be -x%, then that in itself is interesting. But the reason is not necessarily just related to the PDA itself. It is the variation in overall performance of the aircraft from that which would be expected, bearing in mind the variability (or uncertainty) of all the other factors that affect fuel burn for the flight track being modelled.

I think understand how the PDA is being used in the modelling, (Richard and DrB . . I am open to correction if I have it wrong), but perhaps it would be more appropriate to define some other term to describe the variability in overall fuel burn. (DeltaF) Actually this new variable can of course be compared to the known PDA range for MH370.

Am I being overly pedantic? Perhaps.

@Richard, DrB

What I don’t understand in your fuel flow analysis / PDA estimates (and using this as one of the path selection criteria) is how you estimate the initial (19:41) fuel quantity. Can you please explain?

Imo, either it is an unknown (in which case you have an extra degree of freedom in the problem), or it is determined by calculating back and assuming fuel exhaustion (somewhere in the 00:11 – 00:19 interval) in which case you have to work with a fixed PDA.

@Brian Anderson

Switching off an Integrated Drive Generator (IDG) or shedding load from an IDG and/or switching off the Bleed Air System can reduce the fuel consumption of an Engine. I did think of introducing a new term such as Performance Improvement Allowance (PIA) for this case, but found it more confusing having 2 terms PDA and PIA, rather than allowing the PDA to go negative. I agree we are abusing the original definition and intent of the term PDA.

@Richard,

I think two terms are unnecessary, because even if you introduce a new one which is allowed to go negative, the PDA in the model is still an amalgam of the real PDA, and other factors that cause a change in the nominal fuel burn. (e.g. load shedding etc).

It is sufficient to define a new term, say DeltaF, which replaces the current PDA. Then variations identified in the DeltaF, which might be positive or negative, can be compared with the real PDA, and possibly explained by such things as load shedding.

@Brian Anderson

Interesting point – the overall performance degradation from the book figures is related to both the engines and airframe. Airlines use airplane performance monitoring (APM) programs to determine a performance degradation factor for flight planning purposes, based on cruise performance reports sent from the aircraft. The same factor is entered into the FMC to provide the pilots with accurate in-flight predictions of the fuel remaining at flight planned waypoints and destination. Boeing refers to it as the FF (Fuel flow) factor, while Airbus uses the term PERF (Performance) factor.

As an aside, it is possible to have a FF/PERF factor less than zero, because the book level reflects the fleet average of new aircraft and engines. There is inevitably a scatter that leads to performance above and below the book value for newly delivered aircraft and indeed, some older aircraft. We have several B777-300ERs (not new!) in our fleet that have FF factors below zero. Airbus uses a PERF factor as low as -2.0% for new deliveries with certain airframe/engine combinations.

@Andrew,

Yes, it’s an interesting question. I thought that the PDA number related to a particular engine, and stayed with that engine. i.e. increased progressively through the life of the engine.

I understand the concept of the FF, or the PERF, in that it includes variabilities in the airframe too. However, it must be indeterminate on day one, or at least until sufficient cruise data, or data related to a typical flight profile, is collected. Then if an engine is changed out the data collection must begin again.

@Brian Anderson

There is a PDA for each engine, used mainly for engineering purposes. The FF/PERF factor is more relevant for estimating fuel burn, because it reflects the difference between the airframe/engine combination and the book figures. The PDA normally increases through the life of the engine, but the FF/PERF factor might go down if engineering work is done on the airframe that reduces drag (eg seal replacement, flight control/door rigging), or there is an engine change that results in a lower PDA.

The actual FF/PERF factor is ‘indeterminate’ on day one, as you mentioned. For the A330, Airbus has standard factors that it uses at delivery, depending on the engine type. For example, the A330-343 with Trent 772B-60 engines uses a PERF factor of -2.0% at delivery. That factor is adjusted once the aircraft enters service and data is collected using the APM program. The factors are regularly updated to reflect changes in engine/airframe performance, as determined by the APM program. One of our A330s has a PERF factor of -2.7%, and that’s a 15-year old aircraft!

Some references that might be of interest:

Getting to grips with aircraft performance monitoring

Aircraft performance monitoring from flight data

Airbus Regional Seminar – Aircraft performance monitoring

@Andrew, @Brian Anderson: To be clear, the value of 1.5% that we use is the fuel flow (FF) factor, as per the fuel analysis for MH370. We really don’t know the PDAs for the engines. We also don’t know the drag factor, which is used by the FMC to plan and manage the descent. That said, semantics aside, I don’t think that there is a fundamental error in calculating a PDA (FF factor) based on the estimated time of fuel exhaustion, and then comparing that calculated value of PDA (FF factor) to the value that is expected.

9M-MRO Fuel Flow Factors

1. A parameter called “PDA” is used by MAS to predict the fuel loaded for each flight. It is used in the MH370 Flight Plan, and its value is +1.5%, which is a very reasonable value for an average of the fuel flows of 9M-MRO’s two engines in cruise. MAS may be using the term “PDA” in a different fashion than other airlines or manufacturers, who want to keep track of engine and airframe efficiencies separately.

2. As far as I know, there is no other fuel flow efficiency factor used in the MH370 Flight Plan.

3. I believe the “PDA” value used by MAS in their flight planning is based on actual fuel consumption data for that airframe and those engines. In other words, the 1.5% PDA as used by MAS is for 9M-MRO, not just for the engines. Thus the value used by MAS may actually be a fuel flow factor (as an excess % relative to the Boeing fuel flow tables).

4. I have engineering data from ATSB from a prior 9M-MRO flight. This includes frequent readings of both fuel flow meters and both fuel quantity gages. In cruise, the ratio of R/L readings is near 1.02, but it does vary slightly between fuel quantity sensors and the fuel flow sensors, both of which have accuracies of about 1%. Using the fuel quantity sensors, the ratio is 1.021. This implies the R engine will flame out about 16 minutes prior to when the L engine would flame out if the L engine fuel flow were not increased substantially during the INOP condition after R engine flame out. This does occur in practice, and it reduces the time difference between actual R and L engine flame outs below 16 minutes.

5. My estimate of the R engine “PDA” is +2.45% and for the L engine it is +0.45%.

6. There is no need (or means) for us to separate engine and airframe effects for 9M-MRO, and I have used the (combined) parameter “PDA” (or FFF) in the same way as MAS uses it for flight planning.

7. Some of the routes we analyze have predicted “PDAs” (or FFFs) substantially different than +1.5%. That indicates errors in the route parameters, assuming the aircraft is being flown in its normal configuration.

8. Abnormal aircraft configurations are possible which can save (or waste) fuel. One can assume the bleed air is turned off, for instance, which can reduce fuel flows by about 2%. This is equivalent to a reduction in the FFF of 2% (which then gets into negative percentages).

9. It may be less confusing to call the predicted amount of differential fuel flow a predicted fuel flow factor (FFF) rather than a predicted PDA. I don’t object to doing that. Whatever you call it, the value of that parameter, compared to the +1.5% used by MAS, is a vital part of any route feasibility determination.

@DrB: In the “Fuel Analysis” for flight MH370, there is a parameter called “PER FACTOR” and in the “Flight Brief” there is a parameter called “FF FACTOR”. The value of both parameters is P1.5, i.e, +1.5%. Meanwhile, in the FMC, there are two parameters called “DRAG” and “FF” (which get entered on the same line). I don’t see any specific reference to PDA. It would be the FF FACTOR (=PER FACTOR) that gets entered into the FMC.

I don’t think it is worth the effort to rename the PDA parameter. We all understand what is meant.

@Victor Iannello,

You are correct. The MH370 Flight Brief correctly uses the term “FF Factor”.

@Niels:

You asked: “What I don’t understand in your fuel flow analysis / PDA estimates (and using this as one of the path selection criteria) is how you estimate the initial (19:41) fuel quantity. Can you please explain?”

Here is a summary of my fuel/endurance model particulars:

1. Assume Zero Fuel Weight = 174.369 tonnes.

2. Start model at 17:06:43 with 43.8 tonnes total from last ACARS report (with 21.973 tonnes in in L and 21.827 in R tanks).

3. Assume no fuel transfers.

4. Assume in cruise the R engine fuel flow is 2.1% greater than the L engine fuel flow (based on my analysis of prior flights).

5. My fuel model has three periods.

6. Same PDA is used for all 3 periods, and it is selected for MEFE at 00:17:30.

7. First period assumes ECON with CI = 52 at FL350 from 17:07 to 17:33.

8. Second period assumes LRC at FL390. Climb to FL390 starts at 17:33.

9. Third period starts at 18:34 and continues until MEFE. Speed and altitude during the third period are the same as what is being fitted (from 19:41-00:11). Climb or descent, if needed, occurs at 18:34.

10. For the BEDAX LNAV 180 degree route, my predicted fuel weight at 19:41 is 26.8 tonnes.

11. I compute the L and R engine fuel flows and the L and R tank fuel quantities each minute. The R tank goes dry circa 00:08. I estimate there is about 580 kg of fuel in the L tank when the R tank goes dry. Then the L engine fuel flow increases to roughly 3500 kg/hr due to single-engine INOP, and increases further during the descent, and the L engine flames out at 00:17:30. So, I estimate there is about a 9.5 minute difference in flame-out times. The aircraft decelerates beginning at 00:08 during INOP, and I predict the descent begins circa 00:14.

@DrB: There is another possibility related to fuel exhaustion: If either or both of the forward and aft crossfeed valves are open, both engines may draw fuel from either tank, and both engines will flameout at almost the same time without any manual intervention. Andrew once explained that the pumps from one side will dominate over the other side, and so the draw down of the tanks might not occur symmetrically. On the other hand, if the level on one side is higher than the other, that will tend to increase the pressure from the pumps drawing from that side, and could help to maintain nearly equal levels on both sides.

@Victor

@DrB

You could call the performance degradation factor anything you please. I don’t think it matters as long as the meaning is clear. I was only trying to explain that the ‘factor’ has engine and airframe components; it is not a simple engine degradation factor, as I have seen mentioned from time to time.

@Niels

You stated “What I don’t understand in your fuel flow analysis / PDA estimates (and using this as one of the path selection criteria) is how you estimate the initial (19:41) fuel quantity. Can you please explain?”

The calculation of the fuel quantity remaining is based on a number of assumptions:

(1) The Zero Fuel Weight is correctly stated in the Malaysian SIR as 174,369 kg.

(2) The Departure Fuel Weight is correctly stated in the Malaysian SIR as 49,700 kg, left tank 24,900 kg and right tank 24,800 kg. All values ± 50 kg.

(3) The ACARS Fuel Weight at 17:06:43 UTC is 43,800 kg ± 50 kg is correct at reaching the cruise altitude of 35,000 feet.

(4) There were no fuel transfers between the tanks.

(5) There was a climb following diversion to FL390 followed by a change to LRC speed mode.

(6) The right engine fuel consumption is 2.1% greater than the left engine fuel consumption.

(7) There was no load shedding, IDG switched off or Air Bleed System switched off.

(8) The temperature deviation from ISA is correctly calculated from the GDAS data.

At 18:28:06 UTC Bobby calculates 34,571 kg fuel remaining, I calculate 34,490 kg. This is a difference of 81 kg or 0.23%.

We are both quite different from the Boeing analysis which shows 33,524 kg. This is a difference of 1,047 kg from Bobby’s result or 3.03%. Boeing assumes a descent to FL300, where at 210,000 kg aircraft weight the fuel flow/hr/engine increases from 3,277 kg/hr/engine to 3,762 kg/hr/engine.

At 19:41:03 UTC Bobby calculates 26,796 kg fuel remaining, I calculate 26,709 kg. This is a difference of 87 kg or 0.32%.

We both align within 0.5% at 18:28:06 UTC and 19:41:03 UTC.

@DrB

My apologies! I did not see your comment before writing mine. Our comments to @Niels crossed in the wires.

@Niels

You can choose which answer you prefer 😉 The nice problem of writing “@Richard, DrB”.

@Dr B. Thanks for these additional insights on the fuel model background. I understand that your assumption for one engine inop is that the running one goes to max climb thrust per Mike E and Andrew’s reports from simulations? Would you care to speculate how much longer left engine might run if company policy set max cruise rather than max climb thrust as the default for one engine operation?

@paul smithson,

You asked: “Would you care to speculate how much longer left engine might run if company policy set max cruise rather than max climb thrust as the default for one engine operation?”

I am happy to do that calculation if someone can provide the max cruise thrust.

@DrB, Richard

Many thanks for sharing the details of fuel calculations. It is good that your estimates align well, however my main worry remains, which is the unknown flight path between 18:28 and 19:41 with possible altitude and speed changes, hence with possible significant impact on 19:41 fuel quantity.

For example, would it be possible to work with an estimated 19:41 min / max value, and compare the “back calculated” fuel quantity based on fuel exhaustion and ~1.5% “PDA” with this min – max 19:41 range?

Just for a laugh, can we please run the CAPTIO flight path through this model to see how far out it is?

On a more serious note, is the simulation software, or at least the algorithms used to create it, going to be made publicly available? Could it be a GPL project on GitHub?

@Rob

Just for a laugh, can we please run the CAPTIO flight path through this model to see how far out it is?

The CAPTIO flight path is not a candidate path consistant with the assumptions baked into the model. It has course, speed, and altitude changes.

Thanks, Dr B. Unfortunately I am not able to tell you what the max cruise thrust value is. Hopefully another blog contributor may be able to.

@DrB

@PaulSmithson

RE: “I am happy to do that calculation if someone can provide the max cruise thrust.”

The figures are not published in the manuals used for everyday operations. Max cruise thrust is not a ‘certified’ rating and is not used for the calculation of aircraft performance. You would probably only find the figures in some obscure manual used by the performance engineers.

The thrust limit (CLB or CRZ) used during all-engine cruise can be modified by the airline via the FMC Airline Policy page; however, the default value is CLB thrust. The FMC only uses the CRZ thrust limit if the airline decides to modify the default settings, or the crew manually selects the CRZ thrust limit after reaching top-of-climb.

@Andrew. Thanks. Are you saying that the thrust limit for one engine inop is the same as that which has been set for all-engine cruise? And only if that default (all engine cruise) has been changed would we see something different when first engine goes down?

I don’t know whether a “thrifty” operator might prefer to reduce default max thrust available for all engine cruise? With very powerful engines and plenty of surplus thrust, would there be any *practical* performance downside to doing so?

@paul smithson

The thrust limit does not automatically change if an engine fails in the cruise. The pilots would normally activate ENG OUT on the FMC VNAV CRZ page, which changes the thrust limit to CON to provide additional thrust. Otherwise, the thrust limit remains at the setting on the airline policy page (normally CLB, but modifiable to CRZ). Sorry I didn’t make that more clear.

The downside of modifying the cruise thrust limit to CRZ is that less thrust will initially be available if an engine fails in the cruise. Consequently, the speed will decay more rapidly, particularly at altitudes close to MAX, which could have nasty consequences if the crew becomes distracted and doesn’t immediately activate ENG OUT and start descending. If the cruise thrust limit is CLB, there’s a bit more thrust available, which gives the crew a bit more time to analyse the problem before they activate ENG OUT and start descending. That said, the difference isn’t huge.

As far as I’m aware, the main purpose of the CRZ thrust limit relates to performance guarantees that are part of the contractual arrangements between Boeing and the aircraft operator. It has little or no use in everyday operations.

thanks, @andrew.

@DrB

RE: “I am happy to do that calculation if someone can provide the max cruise thrust.”

Rolls-Royce MCT: 312.3 or 343.3kN depending on engine model…

Try pg-8 at the following link:

https://www.easa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/dfu/EASA%20E%20047%20TCDS%20issue%2004.pdf

@George Tilton

Many thanks for the MCT data!

In the MH370 case, the engine is the Rolls Royce RB211 Trent 892-17.

The MCT is therefore 343.3 kN from the linked document you supplied.

@Paul Smithson: The maximum thrust at altitude can be approximated by the sea level thrust multiplied by (Pamb/Po). For instance, at FL350, the altitude correction factor is 0.235.

However, I’m missing the gist of this discussion. As @Andrew said, the difference between Maximum Continuous Thrust and Maximum Climb Thrust is small, and becomes relevant under conditions such as obstacle clearance with one engine inoperative. For instance, in the PMDG 777-200LR model with GE90-110B1L2 engines, at cruise altitude, the values for N1 for CRZ, CLB, and CON thrust limits are 97.4%, 101.0%, and 101.0%, respectively.

@George Tilton

@Richard

RE: ”Rolls-Royce MCT: 312.3 or 343.3kN depending on engine model…”

Note, the ‘MCT’ data that George provided is Max Continuous Thrust, which is a higher rating than Max Cruise Thrust. @paul smithson’s question related to Maximum Cruise Thrust.

@Victor

The discussion with @paul smithson relates to the thrust rating set by the FMC during cruise. That rating is dictated by the setting on the FMC’s AIRLINE POLICY page. It defaults to CLB thrust, but can be modified to CRZ thrust by the airline. @paul smithson originally asked @DrB ”Would you care to speculate how much longer left engine might run if company policy set max cruise rather than max climb thrust as the default for one engine operation?”.

@Andrew: My point is we are down in the weeds. With all the other unknowns (such as having an accurate drag model for the deceleration and having accurately modeled the fuel consumption from 17:07 to the first flameout), for the short amount of time between the first and second flameouts, it makes no material difference whether the thrust was CLB, CRZ, or CON.

@paul smithson,

If I understand Andrew correctly, if no pilot action were taken upon R engine flame-out, the L engine would normally go to Max Climb Thrust (CLB), unless MAS had previously changed the default to Max Cruise Thrust (CRZ). If a pilot subsequently activated ENG OUT, then the thrust limit would change to Max Continuous Thrust (CON).

If I understand the engine data sheet correctly, CON is about 17% less than CLB, the CON fuel flow would be reduced by a similar percentage and the duration between R and L engine flame-outs would be lengthened by that same percentage. This assumes a pilot activated ENG OUT.

It’s not clear to me how much less CRZ is than CON for this engine, but a lower thrust limit reduces INOP fuel flow and lengthens the INOP duration.

@DrB said: If I understand the engine data sheet correctly, CON is about 17% less than CLB

No. Maximum continuous thrust (CON) is slighter HIGHER than maximum climb thrust (CLB) (when there is a difference at all). Meanwhile, maximum takeoff thrust is significantly higher than maximum continuous thrust, as it has a 5-minute rating. Maximum cruise thrust (which is not a parameter that is certified) is several percent less than maximum climb thrust.

Also, although the FMC might default to CLB during cruise by company policy, it is trivial for the crew to change the limit from CLB to CRZ (or CON).

@Victor

RE: “My point is we are down in the weeds.”

Point taken. My post was intended to clarify @paul smithson’s question, which was related to the difference between CLB and CON thrust (you stated “…the difference between Maximum Continuous Thrust and Maximum Climb Thrust is small”). Nevertheless, I agree; the difference between the various thrust limits is small and immaterial given all the other uncertainties. My guess is the difference between the CLB and CRZ thrust fuel flows would amount to about a 30-second difference in the L engine flameout time, given @DrB’s estimated 580 kg of fuel in the L tank when the R tank goes dry.

@Andrew: Thank you so much for your input and your continued interest in the blog.

@Victor

You’re welcome. I just spotted an error in my previous post. I should have said @paul smithson’s question was related to the difference between CLB and CRZ thrust!

@Richard, @Victor, @Dr B. Some of you requested that I share precise path model details. I was not in a position to do so earlier as I have not had time to refine the models during the past 3 weeks. This path model that arises from my work on where (in BTO terms) an FMT “ought” to have occurred, so it starts from there rather from the 1941 ping ring.

I have noodled around this area with various path solutions and this is the best that I can do. The start position is very close (21 microseconds) to where my models “expect” it to be.

The parameters are:

Start 18:32:30Z

Long 95.252 Lat 7.113

LNAV

Initial track angle 190.55

FL 340 (but geo height 35000ft for purpose of BTO calcs)

Constant M0.8455 (initial TAS 499kts)

The model that I am using yields an end point of -39.54, 85.22 (this is the 7th arc crossing ie BTO=18390, rather than position at 001930). BTO residuals are: 8,7,7,-50,11 and BFO residuals are -2.1, -4.3, 4.4, 4.9, 5.4, 5.6 (the last BTO, ping 6, assumes descent of 200fpm).

Perhaps you can get an even better fit with different altitudes and more finely interpolated Wx data. I have simply used the weather array in Barry Martin’s model (0000Z, 250hPa). I did also try using Wx for higher altitudes but I think the fit was poorer and the required M number higher.

I will be particularly interested in what your various fuel models predict for this path.

I have focused primarily on LNAV path solutions to date because TT solutions a) have a 7th arc crossing further north, within the searched area – typically between 38.5S and 39.0S b) invariably have large residuals at ping 6 – requiring a massive slow-down. I say “massive” because it appears to exceed what looks feasible from a combination of greater headwind (or lower temp) over the last stage and longer period with one engine inop before second flameout (which was why I was interested in the Max CRZ vs CLB numbers).

There is, of course, a solution with initial track angle of 191.0 that terminates marginally further south. But as well as requiring slightly higher speed, I have various reasons for preferring the solution mentioned above.

FYI, the 191.0 LNAV path would be something close to:-

Start 18:31:45

Long 95.347, Lat 7.066

M0.8478 (initial TAS 500.5)

Crosses 7th arc at 39.72S

BTO residuals: 15,7,4,-54,10

BFO residuals -2.2 (1840), -4.3,4.4,5.1,5.7,5.8 (last one descending 200fpm)

I’m very pleased to see that the CMH 180 path to 34.2S is still a strong contender after all the learned investigation that has gone into this. It has long seemed the most likely, to me at least. The commentary here is generally of very good quality and still fascinating even after so much time has elapsed since the events themselves. I just wish I had the skills and knowledge to contribute more.

@Victor

Your recent paper is very good. I was thinking about the difference between your approach and the particle filter model used by DTSG 5 years ago.

It seems their particle filter generates “infinite” flight paths based on their defined maneuvering model and ranks them using the BTO/BFO data to create the PDF centered at 38 S around arc 7.

It seems that you define each candidate profile based on selecting autopilot navigation mode, speed mode, and altitude mode and rate it based on the BTO/BFO data. The 34.4 S crossing on arc 7 provides the best fit.

So for the case of an inactive pilot, the “infinite” random flights and large sample of reasonable routes confirms an arc 7 search of 34.4 to 38 S.

This appears to be a very good independent confirmation of the DSTG work for an inactive pilot.

I missed the discussion where it was determined that there could be no active pilot after 19:41.

@Ulric,

The 19:41-00:11 route which appears most likely is either LNAV (geodesic) or a Constant True Track at 180 degrees. No possible Constant Magnetic Heading routes have ever been identified as a region of Interest.

@paul smithson,

There is no need to assume a slight descent at 00:11 in order to match the BFO then. To my knowledge, no end-of-flight model predicts a descent beginning before or at 00:11. Both my end-of-flight model and Boeing’s simulations predict the descent beginning several minutes after 00:11.

@Hank,

There is no “determination” (or proof) about the presence or absence of active piloting after 19:41. However, it is quite striking that there is one and only one route for which no active piloting after 19:41 is needed in order to completely match the BTOs, BFOs, their known correlations, and the endurance. In my opinion, the presence of a unique solution is a likely indicator of correctness. At the very least, it is the most likely place to search next. If that fails, then, absent new revelations, searching elsewhere is not worthwhile because the number of possible solutions with maneuvers after 19:41 is boundless.

@DrB. The “only one route” you mention would be consistent with there being an active pilot who intervened only at fuel exhaustion, pushing the nose down into a steep final dive, APU start leading to the final transmissions.

This possibility by-passes non-replication of the timing/descent combinations of those transmissions by those unmanned Boeing simulations. Thus adding this to the unmanned possibility should enhance the search prospects of that alone. Also it can explain why there was insufficient time for IFE set-up, a piloted glide needing another explanation for that.

Thus I think that its inclusion would strengthen the case for a search based on that route.

@Dr B

Sorry, I meant the CMT 181 route identified in the table at the top of the article. You’re quite right and that will teach me to post when I’m bleary eyed.

Thanks for your comments, Dr B. Without descent the BFO at 0011 would be 9.2Hz, which looks high – particularly in comparison to the values at ping 4 and 5.

If it is not too much trouble – and at your convenience, I would be interested to see how he BTO/BFO/PDA for the 190.55 model referred above come out using your path modelling tool.

@Paul Smithson

You stated: “@Richard, @Victor, @Dr B. Some of you requested that I share precise path model details.”

Start 18:32:30Z

Long 95.252 Lat 7.113

LNAV

Initial track angle 190.55

FL 340 (but geo height 35000ft for purpose of BTO calcs)

Constant M0.8455 (initial TAS 499kts)

I will run this through my model as soon as possible.

I am currently busy with re-running the flight paths in the ROI table (Figure 8), where you kindly pointed out an error.

Thank you, @Richard – much obliged.