As expected, the Safety Investigation Report on MH370 offered no explanation on the cause of the disappearance. “The answer can only be conclusive if the wreckage is found,” Kok Soo Chon, head of the MH370 safety investigation team, told reporters. However, Malaysian investigators did surmise the plane was intentionally diverted, likely due to unlawful interference by a third party. The Malaysia investigators also believe the disappearance could not have been a deliberate act by the pilots based on their background, training, and mental health.

As all the passengers and crew were cleared, who was this third party that diverted the plane? How can Malaysian investigators ignore that the captain had the best opportunity and capability to divert the plane? How does the compressed timeline of the diversion fit any other possibility if the diversion was intentional? It is understandable that the Safety Report did not apportion blame to the captain. However, it is not understandable that the report deflected blame to an unnamed third party.

The report, including the appendices, is 1,423 pages, and it will take some number of days for independent investigators to thoroughly pore over the entire contents and provide thoughtful comments and analysis. However, based on an initial review, there are some technical questions and inconsistencies that are apparent:

Radar data

The report provides more details about the radar data, but Malaysia fails to provide the raw military data that would allow an independent review. (The civilian radar data was previously made available through an unsanctioned release, and published in a previous blog post.) The military radar includes speed and altitude data, in addition to latitude and longitude at each capture. However, some of the variations in speed and altitude are beyond the capabilities of the plane. For instance, the measured speed and altitude at 18:01:59 UTC are 589 knots and 58,200 ft. One minute later, the speed and altitude are recorded as 492 knots and 4,800 ft. The investigative team was warned that the altitude and speed extracted from the data are subjected to inherent error. The only useful information obtained from the Military radar was the latitude and longitude position of the aircraft as this data is reasonably accurate. How the military radar data can be so far out of calibration is unexplained.

After all this time, we still can’t be sure what radar data is available as MH370 passed over the Malacca Strait. According to the main body of this report, the radar target disappeared at 18:01:59 near Pulau Perak, and re-appeared at 18:15:25 along airway N571 between waypoints VAMPI and MEKAR, disappearing at 18:22:12 about 10 NM past MEKAR. However, in an Appendix 1.6E, Boeing reports that after 18:01:59, there was only one capture at 18:22:12. It appears that the radar data provided to Boeing is consistent with the data provided to the ATSB, but Malaysia claims there were additional captures along airway N571 between 18:15:25 and 18:22:12.

We also can’t be sure when the unidentified radar targets captured over the Malay peninsula were first recognized as MH370. According the Safety Report, On the day of the disappearance of MH370, the Military radar system recognised the ‘blip’ that appeared west after the left turn over IGARI was that of MH370. Even with the loss of SSR data, the Military long range air defence radar with Primary Surveillance Radar (PSR) capabilities affirmed that it was MH370 based on its track behaviour, characteristics and constant/continuous track pattern/trend. Therefore, the Military did not pursue to intercept the aircraft since it was ‘friendly’ and did not pose any threat to national airspace security, integrity and sovereignty. In light of the claim that the military was fully aware of the path of MH370, it is not explained why the initial Search and Rescue operations were coordinated in the South China Sea to the east of Malaysia, and proceeded for some number of days before they were moved west of Malaysia to the Indian Ocean.

Pilot Simulator Data

Citing the Royal Malaysian Police (RMP) report from May 2014, the Safety Report says It was also discovered that there were seven ‘manually programmed’ waypoint4 coordinates … that when connected together, will create a flight path from KLIA to an area south of the Indian Ocean through the Andaman Sea. These coordinates were stored in the Volume Shadow Information (VSI) file dated 03 February 2014. The function of this file was to save information when a computer is left idle for more than 15 minutes. Hence, the RMP Forensic Report could not determine if the waypoints came from one or more files.

What is not mentioned is that certain values that were common to the data sets indicate that these files were likely from the same simulation. This was first documented in a technical paper I co-authored with Yves Guillaume, and summarized in a previous blog post. Also included in the previous blog post were statements from the ATSB indicating that the chronological order of the data sets matches a flight departing KLIA, flying over the Malacca Strait, continuing past the Andaman Islands, turning to the south, and exhausting fuel in the SIO, in the same order that the progressively depleting fuel levels suggest. The time values also indicate that the flight session lasted for about one hour, suggesting the position of the aircraft in the simulation was manually advanced and the fuel levels manually depleted.

There are other strange facts surrounding the simulator data. For instance, Malaysia does not explain why only fragments of the data files were recovered, as the reconstruction of the entire contents of the data files should have been possible using the data in the Shadow Volume. The missing portions of the data files include important information that would be stored in the flight management computers (FMCs), including flight plans. Also, the time stamp data that was included in the data files that were made available to the ATSB by the Australian Federal Police was not included in the RMP report.

The RMP conclusion that there were no unusual activities other than game-related flight simulations is odd considering the extraordinary coincidence that a simulated flight including a departure from KLIA and ending in fuel exhaustion in the SIO was recovered after the disappearance.

Investigation of the Flaperon

After the flaperon was recovered from Reunion Island, which is sovereign territory of France, French scientists performed tests to determine the flaperon’s provenance, to analyze the attached marine biology, to determine its buoyancy and other hydrodynamic characteristics, and to investigate the damage to determine how the flaperon separated from the aircraft. To the French team, it appeared that the flaperon impacted the water while still attached to the aeroplane and that at the time of the impact it was deflected. The implication is that water forces from an attempted ditching caused the flaperon to separate rather than in-flight during a high speed descent. The French were careful to advise that this is only an hypothesis because of the limited data made available to them by Boeing, and because of the complicated dynamics of the impact mechanics.

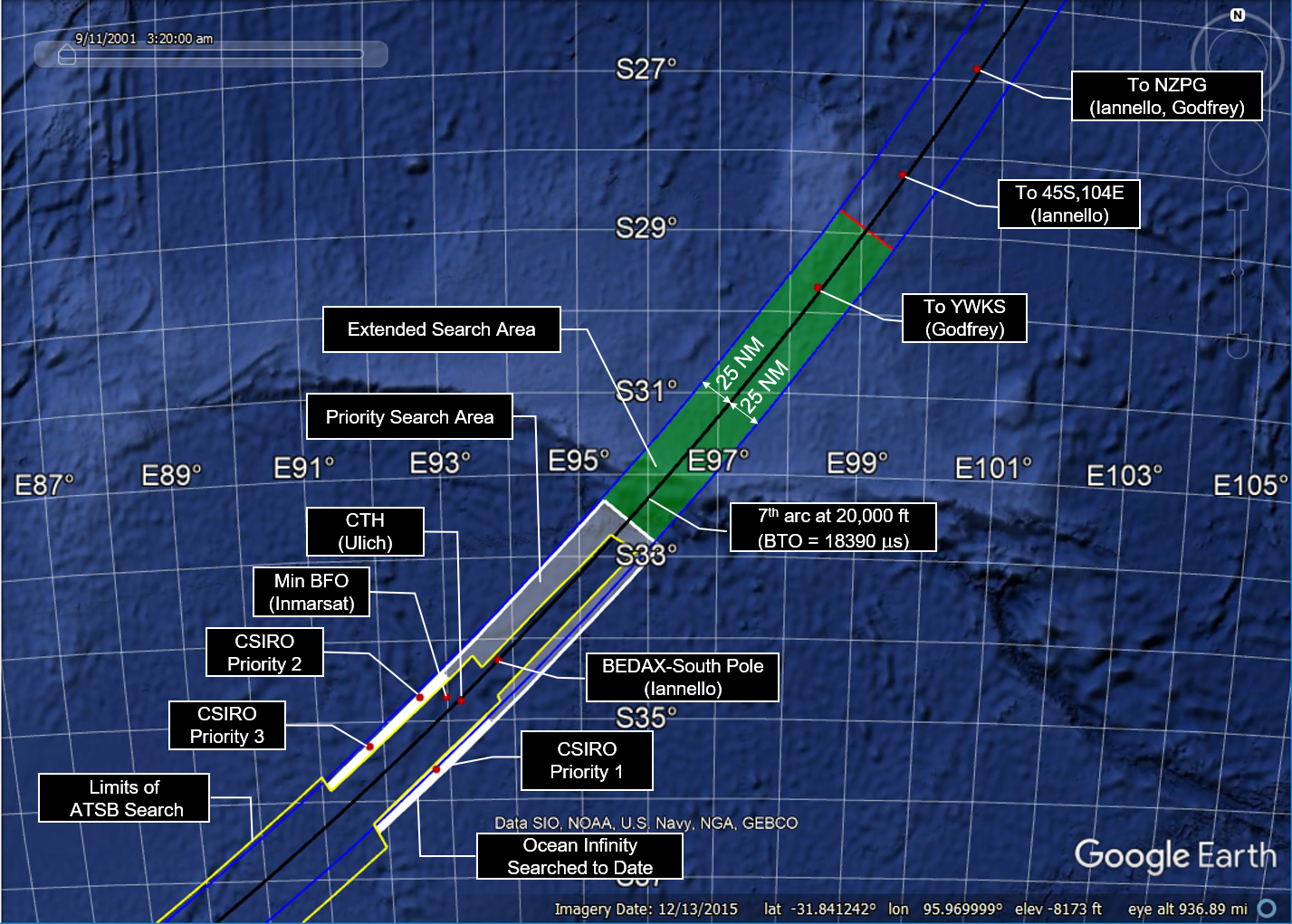

Nonetheless, if it can be proven that the aircraft was in a controlled descent at the time it impacted the ocean, the distance from the 7th arc could be greater than 120 NM, as there could have been a long glide after fuel exhaustion. A controlled descent after fuel exhaustion would also leave open the possibility of pilot navigational inputs after 19:41, and possible paths would include crossing the 7th arc over a large range of latitudes. These unknowns would make it very difficult to define a new search area of a manageable size. For this reason, it is critical that mechanism that led to separation of the flaperon be determined with a higher level of certainty.

First Officer’s Cell Phone Connect

The First Officer’s cell phone registered on a cell tower as MH370 passed to the south of Penang Island. Although it would be unlikely that a cell phone connection would persist long enough to complete a call, a cell phone registration of short duration and at cruise altitude is not that uncommon.

Considering the large number of Malaysian passengers and crew that were likely carrying cell phones compatible with the Malaysian cell network, and with some fraction of those phones likely in an operational configuration during the flight, it is odd that other cell phone registrations did not occur. It is unexplained whether or not a systematic review of the cell phone numbers of all passengers and crew was ever performed.

Final Comments

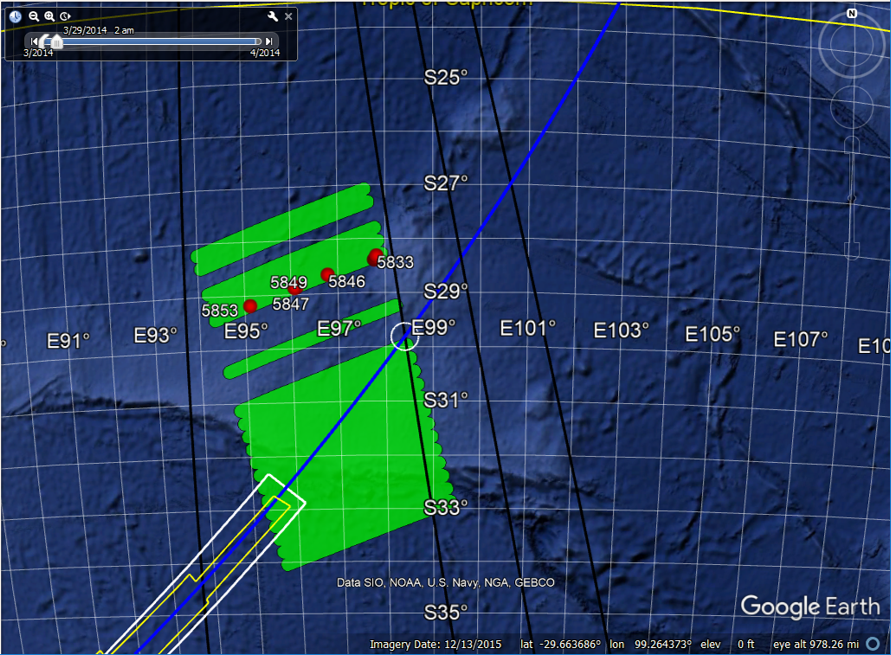

It is unlikely that another search for MH370 will occur unless a case can be made that there is a reasonable probability of success. Unfortunately, the Safety Report raises more questions than it answers, and it will be difficult to use the information in the report to define a search area of a manageable size. The answers to some questions will not be known until the flight data recorder is recovered. However, the answers to other questions are known to Malaysian authorities today. Any remaining chance to find MH370 squarely rests on the willingness of the new Malaysian administration to cooperatively work with official and independent investigators.